For the Defence of the Caucasus

In this article, you can read a short text about the Caucasus operations, the deportation of Chechens and Ingushs organised by the Soviets, and then about the medal given for the Defence of the Caucasus.

About the Battle of the Caucasus

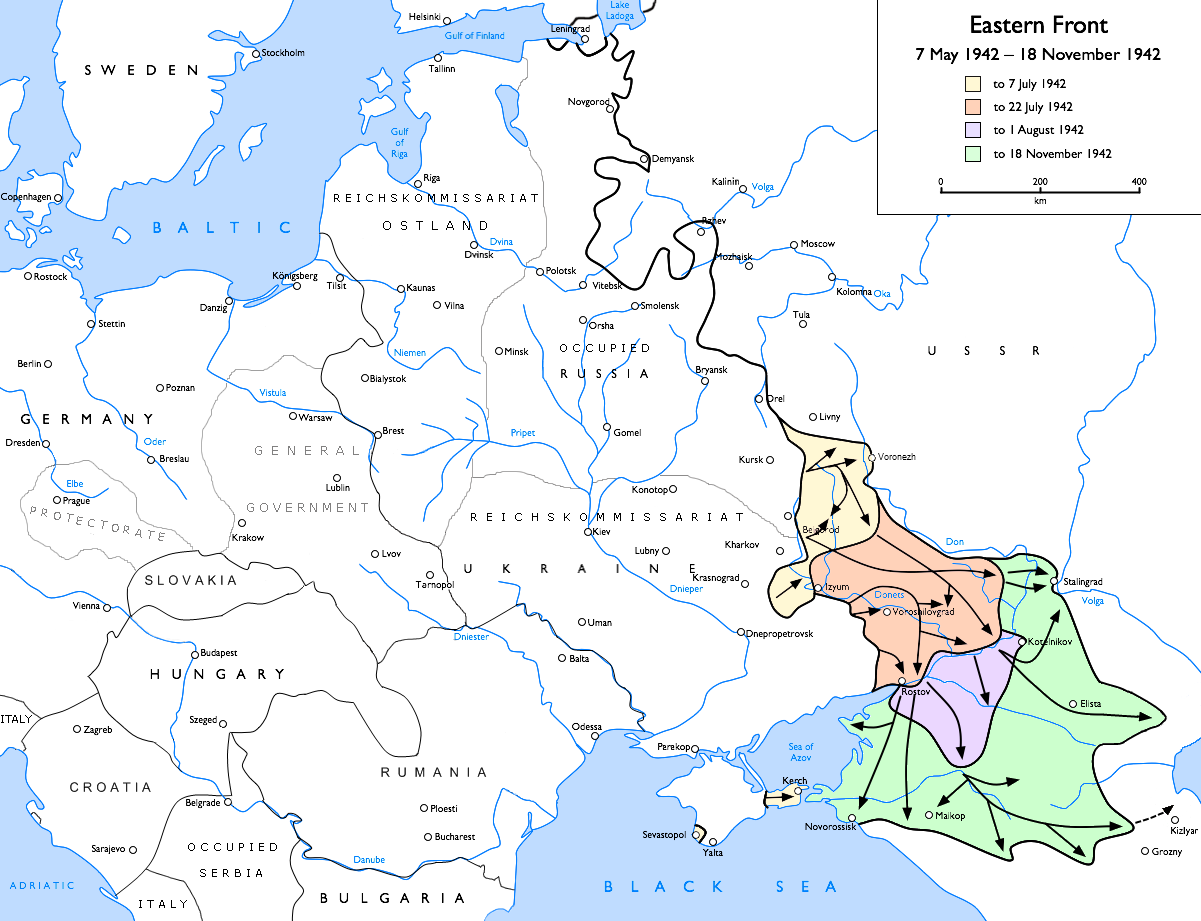

In the summer of 1942, Adolf Hitler launched a major offensive into the Caucasus region of the Soviet Union, known as Operation Edelweiß. The primary goal of this campaign was to capture the oil-rich areas of Maikop, Grozny, and ultimately Baku. Germany faced a growing oil shortage then, and securing these fields was essential to sustaining the Wehrmacht’s mobility and fueling the broader war effort. Hitler also believed denying these vital resources to the Soviet Union would severely weaken its capacity to fight. The attack on the Caucasus was part of a broader strategic plan called Case Blue, which also included the simultaneous advance toward Stalingrad.

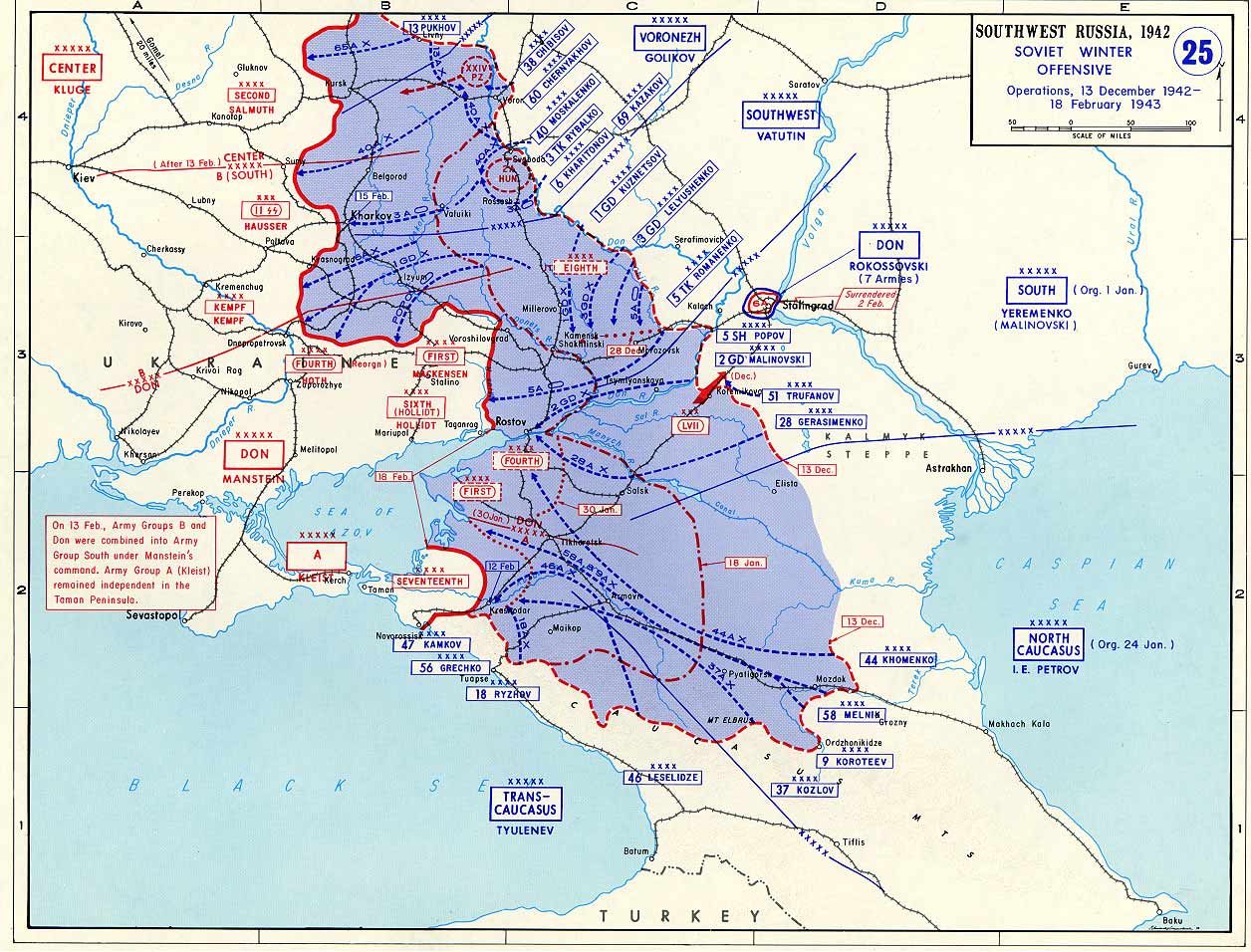

It can be divided into two main phases: the German offensive phase, July 1942 to early 1943 — Operation Edelweiß aimed to capture oil fields but stalled in the mountains; and Soviet counteroffensive and liberation: January to October 1943 — Soviet forces pushed the Germans out, culminating in the recapture of Novorossiysk and the Taman Peninsula.

The Battle of the Caucasus caused heavy losses on both sides. The Soviets suffered about 450.000 casualties (killed, wounded, or missing), while German and Axis forces lost around 100.000-150.000 troops. The Battle of the Caucasus ended in a Soviet victory, with the Red Army defending key oil fields and forcing a complete German retreat by late 1943. For Germany, the campaign failed to secure vital resources, marking a turning point in their decline on the Eastern Front. The German drive into the Caucasus and the Battle of Stalingrad were closely linked in time and strategy, and the failure at Stalingrad directly contributed to the collapse of German ambitions in the Caucasus. While Axis troops participated in this operation, they did not build concentration camps. Prisoners (Jewish people, for example) were held for a couple of days or hours in some rooms in a form of arrest, and then were executed. As in many other regions, war crimes, such as murdering civilians, were present.

Deportation of the Chechens and Ingush after the end of the operation

In 1940, Khasan Israilov led a rebellion of Chechens in Galanchozh. It was partly inspired by how the Finns fought against the Soviet attack on their country in the Winter War of 1939.

Up to 800 people allegedly participated in the unrest, which lasted from October 28 to November 3, 1941. Three combat aviation units were called in to suppress the “unrest”, and mountain villages were bombed. However, reports of unrest are based exclusively on data from the central office of the NKVD of the USSR. According to other data, including information from responsible persons who were directly in the areas mentioned above during this period, there was absolute calm in the mountains, and the bombing of the mountainous regions was a shock for both residents and for the employees of the regional committee of the Communist Party sent to the area.

During World War II, the Soviet government said that the Chechens and the Ingush were working with the Axis powers. Their goal as invaders was to get to the oil riches around Baku in the Azerbaijan SSR, which Plan Case Blue was all about. German paratroopers led by saboteur Osman Gube arrived near the village of Berezhki in the Galashkinsky district on August 25, 1942, to plan anti-Soviet actions. However, they could only find 13 people in the area to join them.

17.413 Chechens joined the Red Army and were awarded 44 decorations, while 13.363 joined the Chechen-Ingush ASSR People’s Militia, ready to defend the area from an invasion. By contrast, Babak Rezvani points out that only about 100 Chechens collaborated with the Axis powers.

About 20 million Muslims lived in the USSR. The government feared a Muslim uprising could spread from the Caucasus to Central Asia. The deportation had been planned since at least October 1943, and 100.000 NKVD soldiers and 19.000 officers from all over the USSR participated. At least a quarter of the 496.000 Chechens and Ingush who were deported died. The effects on the population were terrible and far-reaching. Archive records show that more than 100.000 people died or were killed during the transports and roundups, as well as in their first years as refugees in the Kazakh and Kyrgyz SSRS and the Russian SFSR, where they were sent to many forced villages. Chechen sources say that 400.000 people died, but they think that a bigger number were sent away.

Many people who were being deported died on the way, and many more died in the challenging conditions of exile, mainly because they were exposed to so much heat. It would get as cold as -50 °C in the Kazakh SSR in the winter and warm up to 50 °C in the summer. The waggons were locked from the outside, and there was no water or light inside during the winter. Sometimes, trains would stop and open the waggons to bury the dead in the snow. It was against the rules for people in the train stations to help sick travellers or give them water or medicine.

Description of the medal and requirements

The obverse of the medal depicts Elbrus. At the bottom, at the foot of the mountain, there are oil derricks and a group of moving tanks. Silhouettes of aeroplanes can be seen above the mountain peaks. At the top of the medal is an inscription along the circumference, “FOR THE DEFENCE OF THE CAUCASUS”. The medal’s obverse is bordered by a figure rim, depicting bunches of grapes and flowers. At the top of the rim, there is a five-pointed star. At the bottom of the rim is a ribbon with the letters “USSR” and an image of a hammer and sickle between them. On the reverse side of the medal is the inscription “FOR OUR SOVIET MOTHERLAND”. Above the inscription is an image of a sickle and hammer. All inscriptions and images on the medal are convex.

The medal is connected to a pentagonal block with an eyelet and a ring, covered with a silk moire ribbon of olive color, 24 mm wide. In the middle of the ribbon are two white stripes, 2 mm wide, separated by an olive strip of the same width. Along the edges of the ribbon are blue stripes, each 2.5 mm wide.

The medal was established by the Decree of the Praesidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on May 1, 1944. The Medal “For the Defence of the Caucasus” is awarded to all participants in the defence of the Caucasus – servicemen of the Red Army, Navy and NKVD troops, and civilians who took direct part in the defence.

The award was made:

- To persons in military units of the Red Army, Navy and NKVD troops – by commanders of military units, and to persons who left the army and navy – by regional, city and district military commissars at the place of residence of the awarded persons;

- To civilians – participants in the defense of the Caucasus – by the Stavropol and Krasnodar regional Councils of Workers’ Deputies, the Praesidiums of the Supreme Soviets of the Georgian SSR, Azerbaijan SSR, North Ossetian ASSR and Kabardian ASSR.

The Medal “For the Defence of the Caucasus” was awarded to military personnel and civilian employees of units, formations and institutions of the Red Army, Navy and NKVD troops only to those who participated in the defence of the Caucasus for at least three months in the period July 1942 – October 1943.

The Medal “For the Defence of the Caucasus” was awarded only to those civilians who participated in the defence of the Caucasus in the period July 1942 – October 1943, as well as to those who took an active part in the construction of defensive lines and fortifications from the fall of 1941.

Participants in the defense of the Caucasus, both from among the military and from the civilian population, who were wounded during the defense or awarded orders or medals of the USSR for the defense of the Caucasus, were awarded the Medal “For the Defense of the Caucasus” regardless of the length of participation in the defense.

By 1962, the medal had been awarded to about 580.000 people. By 1985, the Medal “For the Defence of the Caucasus” had been awarded to 870.000 people.

The Southern Bow

“The Southern Bow” is an unofficial name in military history and phaleristics for a set of USSR medals from the Great Patriotic War: “For the Defence of Odessa”, “For the Defence of Sevastopol” and “For the Defence of the Caucasus”. Most of those awarded all three medals were sailors of the Black Sea Fleet, marines and ship crew members. According to some estimates, no more than 1000 people were awarded the complete “Southern Bow” during the war. Veterans are highly respected holders of the Southern Cross, since the set indicates that the person had gone through the most challenging stages of the war on the southern flank of the front. Due to the general colour scheme of the ribbons, they visually stand out among other awards.

My medal

It was my first Soviet medal out of the regional defence series. I found it and ordered from Poland. I find it most beautiful of all the defensive series.